To access material, start machines and answer questions login.

Found an issue in this room? Leave a message in Discord and someone will tag me if I don't see it :)

Reminder This is a walk through room with no extra points for first bloods. Please take your time, copy the copy and experiment with it.

The attached file is this entire room, but as a PDF. If you are having accessibility issues with this room, refer to the PDF which may be much better interpreted.

The Crab is Rust's mascot and is taken from here. All other images are taken from Undraw.

Introduction

Rust is a new programming language created in 2015 by a small team of people, and later adopted by Mozilla (the organisation that created & maintains Firefox).

It is a compiled low level language, which aims (and succeeds) to be the same speed as C++, but while incorporating some higher level language features from fan-favorites such as Python or JavaScript.

Rust has 3 goals:

- Fast

- Secure

- Productive

Fast

Rust aims to be similar in terms of performance to C++.

Rust is statically typed, which means the data type of a variable is known at compile time. This allows the compiler to optimise the code further than if we didn't know the types.

Rust does not use garbage collection (despite being a low level programming language). Garbage collection is where the program attempts to reclaim memory from garbage. Garbage is memory occupied by objects that are no longer in use by the program.

Go, a high level programming language similar syntactically to Python but is fast & compiled, uses garbage collection. This caused a massive overhead at Discord, which forced them to switch from Go to Rust. https://blog.discord.com/why-discord-is-switching-from-go-to-rust-a190bbca2b1f

Something to note is that Python and JavaScript use garbage collection. These abstractions may cause issues (as in Discord's case), which is why many choose a low level programming language.

Secure

Rust is completely memory safe. This means that exploits involving memory aren't possible in Rust, unless you explicitly specify unsafe Rust code.

The Microsoft Security Response Centre states that 70% of all CVE's MSRC assigns are memory safety issues. In Microsoft's own words:

"This means that if that software had been written in Rust, 70% of these security issues would most likely have been eliminated. And we’re not the only company to have reported such findings."

Sometimes programmers must perform unsafe operations. Rust provides tools to wrap these unsafe actions so unsafe code can be statically enforced by the Rust compiler.

The memory safety is guaranteed by the concept of ownership. All Rust code follows these rules:

- Each value has a variable, called an owner.

- There can only be one owner at a time.

- When the owner goes out of scope, the value will be dropped.

Values can be moved or borrowed between variables, but no value can have more than 1 owner.

Let's see an example of Python failing with this:

squares = (val * val for val in range(100))

print(min(squares))

print(max(squares))

What we want is:

0

9801

>>> print(min(squares))

0

>>> print(max(squares))

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: max() arg is an empty sequence

In Rust, the same code is:

fn main()

let squares = (0..100).map(|val| val * val);

println!("{:?}", squares.min());

println!("{:?}", squares.max());

}

When we try to compile this, Rust tells us:

error[E0382]: use of moved value: `squares`

--> ownership.rs:4:21

|

3 | println!("{:?}", squares.min());

| ------- value moved here

4 | println!("{:?}", squares.max());

| ^^^^^^^ value used here after move

|

= note: move occurs because `squares` has type `std::iter::Map<std::ops::Range<i32>, [closure@ownership.rs:2:31: 2:40]>`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

I'll talk more about this in a later task, but the important part is that Python allows functions to alter variables they do not own, whereas Rust doesn't.

PS: Notice how the Rust compiler explicitly points out the values, the lines, the exact characters, where the error occurred as well as a full error message explaining why it won't allow that code. Whereas Python simply said max() arg is an empty sequence.

Productivity

Rust's 3rd largest goal is a strange one. Productivity!

Rust provides all of the tools developers need to be productive, shipped with the platform itself.

Note: The below list is read as:

- Tool

Explanation of the above tool.

Some of these include:

- Cargo

Rust's version of NPM or PyPi. Download packages others have created.

- Clippy

Microsoft Clippy, but re-imagined for Rust to aid with development.

- RustFmt

Automatically formats Rust code

- Cargo Test

A built in testing application created by the Rust developers.

- Cargo docs

Automatically generate documentation for your code, using documentation comments (written in Markdown). This documentation is then sent to docs.rs upon publishing to Cargo. Not to mention that examples written in documentation are automatically tested for you. No more untested documentation examples!

- Rust-Analyzer

Think IDE but more intelligent. Rust Analyzer clearly labels what is wrong with your code, why it is wrong, the exact characters that conflict and cause the error, and 90% of the time it provides an "auto-fix" function that automatically fixes these errors for you.

- The Rust Book & Docs

Rust has a book, called The Book which details everything you could want to know about Rust. Neatly chaptered, easily searchable and at your disposal for free. If this isn't good enough, thanks to Rust's documentation comments almost every library you'll use will have extensive documentation online.

With all of these tools at your disposal, it is incredibly rare to compile a Rust program and have bugs in it. In fact, I have only experienced this once. 99% of the time, the tooling and language will have picked up on it long before I hit compile.

Conclusion

If you are looking for something extremely fast and memory safe but while maintaining good productivity, Rust is the language for you.

As Pentesters our job is offering solutions to developers. Telling Python developers that a low-level language is a good alternative sounds wacky at first.

But Rust can hold your hand, as it supports calls from functions written in other languages (foreign function interfacing).

We can use Rust to rewrite security or performance critical code which will cooperate with our existing codebase.

Here's an example of calling C code extern "C" {

fn abs(input: i32) -> i32;

}

fn main() {

unsafe {

println!("C believes that the absolute value of -3 is: {}", abs(-3));

}

}

What famous company switched from Go to Rust, mentioned in this task?

Microsoft Security Centre reports what percentage of CVE's they assign are memory safety issues? Include the % sign.

What is Rust's version of NPM or PyPi?

Before we dive into the language, let's install Rust.

Rust recommends using the tool rustup to manage multiple versions of Rust. If you are familiar with Python, you may have used virtualenvs to achieve a similar result. That is, different versions of Python on the same machine.

This is another great tool created by the Rust team for productivity.

Install RustUp with this command:

curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf https://sh.rustup.rs | sh

This command can also be found on the Rust website https://www.rust-lang.org/tools/install

This command will install the stable version of Rust for your OS.

Rust comes in 3 flavours. Stable, Beta, and Nightly.

Stable is the latest stable release of Rust (stable releases are usually shipped every 6 weeks). Beta updates periodically. Nightly updates when the language itself updates.

Now, let's install some Rust tools to aid our development.

The command we just ran also installs Cargo,

Cargo is the package manager for Rust. All the packages get uploaded to https://crates.io and does a lot of cool things.

The 3 core Cargo commands are:

cargo installInstall a package from Crates.io

Cargo publishPublish a package to crates.io

Cargo updateUpdates all of the local packages

But, since we are developing RustCode there are 3 more important commands

Cargo testRun the tests for our code

Cargo fmtRuns the formatting tool. This tool automatically formats your code (apply the argument --all to format all code). Similar to Python's Black but built in.

Microsoft Clippy but for Rust! Clippy will point out common errors in your code and help you correct them.

Community tools

There is one tool, that is a community based tool — that is seen as absolutely essential to the Rust ecosystem.

That tool is Rust-Analyzer. Imagine an IDE but smarter and more advanced. Rust-Analyzer will analyse your code as you write it, spot errors before you compile & provide an auto-fix option to automatically fix the errors.

Rust-Analyzer states that their most supported version is VS Code, but they are available on many other platforms.

Something cool to note is that the main tools of Rust are written by the Rust developers themselves. In languages like Python, we may argue over whether setuptools or poetry is right. Or whether pytest is better than unittest. Arguing over the right tool to use is procrastination. Rust says "these are the tools you will use" and that's it. This boosts productivity, as you don't have to worry about what tools to use but can impede development as the tool may not be fully complete.

How do we install the package rustscan using cargo?

What command do we run to format our code?

It wouldn't be a programming tutorial without a basic "Hello, World!".

It wouldn't be a programming tutorial without a basic "Hello, World!".

Create a new folder, and in the terminal type:

cargo init

This makes Cargo initialise a new Rust repository. Cargo will take care of most of the work for you.

The file structure is as follows:

- Cargo.toml

- src/

- main.rs

cargo.toml is the configuration file for our Rust project. It includes our dependencies, project name, authors, the version of Rust we are using and more.

When we have just ran cargo init, our file will look like this:

[package]

name = "Hello_world"

version = "0.1.0"

authors = ["bee <bee@fake.com>"]

edition = "2018"

# See more keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

[dependencies]

Our main.rsfile in the folder src is the main file where we write our code. Every single Rust project must have a main file, and every main file must have a main function.

fn main() {

println!("Hello, world!");

}

Fun fact In the original C book, "Hello, World!" is stylised with a capital letter on the word world.

In Rust, we use curly braces to denote blocks of code. And a semi-colon to express the end of an expression.

To print in Rust, we use the macro println!.

We know println is a macro, as it is called with an exclamation mark. Macros, in a nutshell, allow us to write code that writes more code. To put it even simpler, we can create our own syntax that translate to different code.

To run this program, we execute:

cargo run

This should result in:

➜ cargo run

Compiling hello_world v0.1.0 (/tmp/hello_world)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.21s

Running `target/debug/hello_world`

Hello, world!

This command:

- Compiles the code with the unoptimised build (to increase the speed of compilation)

- Runs the code

You'll also notice a new folder has been created, target.

target contains the binaries for our project.

- Cargo.toml

- src/

- main.rs

- target/

- debug/

= build/

- deps/

- examples/

- hello_world

- hello_world.d

- incremental/

Right now, the only important file is hello_world

This file is actually the binary for our program.

We can tell its a binary by running ls -l in the directory

drwxr-xr-x - bee 31 Jul 23:35 build

drwxr-xr-x - bee 31 Jul 23:35 deps

drwxr-xr-x - bee 31 Jul 23:35 examples

.rwxr-xr-x 2.9M bee 31 Jul 23:35 hello_world

.rw-r--r-- 72 bee 31 Jul 23:35 hello_world.d

drwxr-xr-x - bee 31 Jul 23:35 incremental

To build our project without running it, run:

cargo build

And now we can run the binary directly.

./target/debug/hello_world

This is exactly the same as cargo run, but 2 commands.

When we want to build our project and optimise it, run it with the release profile:

cargo build --release

Use the normal cargo build for quick checking of the code. Use the release argument to optimise the code to the maximum possible that the Rust compiler will allow.

We call --release a profile, specifically the release profile. The Rust compiler has different levels of optimisation depending on what you want.

What character represents a macro?

What does every Rust project need as a file?

If we wanted to add a dependency to our Rust project, what file would we edit?

How do we run our Rust project?

How do we build the project RustScan with the release profile (most optimised)?

What folder are the release binaries stored in?

How many release profiles does Rust have using optimisation level?

All variables, by default, are immutable in Rust.

This is a safety feature, but also a productivity feature. Variables that don't change mean you don't have to track down when the value changed, and immutable variables are great for concurrency

Let's see this in action.

fn main() {

let x = 5;

println!("The value of x is: {}", x);

x = 1;

println!("The value of x is: {}", x);

}

This code does not compile**.** It returns with the error:

error[E0384]: cannot assign twice to immutable variable x``

--> src/main.rs:4:5

|

2 | let x = 5;

| -

| |

| first assignment to `x`

| help: make this binding mutable: `mut x`

3 | println!("The value of x is: {}", x);

4 | x = 1;

| ^^^^^ cannot assign twice to immutable variable

The error tells us everything we need to know.

cannot assign twice to immutable variable

This is telling us that we are assigning a value to an immutable variable (a variable that cannot be changed), twice. Which cannot happen.

It is important we get compile-time errors, as this can lead to bugs and undefined behaviour — which can lead to insecure code. In Rust, once an immutable variable is set Rust guarantees it will never change in its lifetime.

To make a variable mutable, we place the mut keyword in front of it like so:

fn main() { let mut x = 9; println!("The value of x is: {}", x); let x = 4; println!("The value of x is: {}", x); }

This code compiles & runs correctly:

➜ cargo run

Compiling hello_world v0.1.0 (/tmp/hello_world)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.14s

Running `target/debug/hello_world`

The value of x is: 9

The value of x is: 4

Being unable to change the value of a variable might have reminded you of another programming concept that most other languages have: constants. Like immutable variables, constants are values that are bound to a name and are not allowed to change, but there are a few differences between constants and variables.

Refer to this code for the tasks.

Question 1

fn main() {

let x: u32 = 5;

println!("The value of x is: {}", x);

x = "hello";

println!("The value of x is: {}", x);

}

Question 2

fn main() {

let x: u32 = 5;

println!("The value of x is: {}", x);

x = 5;

println!("The value of x is: {}", x);

}

In question 1, does this code compile? T(rue) or F(alse)

What is the error code returned by question 1?

Does the code in question 2 compile? T(rue) or F(alse)

What is the error message returned?

Rust also has constants. These are values that aren't just immutable by default, but are always immutable.

Rust also has constants. These are values that aren't just immutable by default, but are always immutable.

Constants can be declared in any scope, including the global scope. This means that we can use their value in any part of our code, or in multiple places at once.

Constants can only be constant, they cannot be set to a function call or any other value that may change at runtime.

We declare constants with the const keyword like so:

const HUNDRED_THOUSAND: u32 = 100_000;

Notice how in Rust, we can use the _ character to denote a space in number without it affecting the value itself. This is purely for readability.

Also note that it is tradition to name a constant in all uppercase.

Shadowing

I'm going to show you something that might not make sense at first.

fn main(){

let x = 6;

let x = x + 1;

println!("{}", x)

}

This is called shadowing. Rustaceans (Rust programmers) say that:

"The first variable is shadowed by the second"

Which means the second variables value appears when used. We can change the type of an immutable variable once it has been defined.

Here's an explanation from the official Rust docs about this principle (edited to match the example)

"This program first binds x to a value of 6. Then it shadows x by repeating let x =, taking the original value and adding 1 so the value of x is then 7."

By using let, we can perform transformations on the variable but have the variable still be immutable after all the transformations have completed.

We're effectively creating a new variable with the let keyword, which means we can change the type of the value.

let word = "hello";

let word = word.len();

Which is allowed.

However, if we tried to use mut, it wouldn't be allowed — as mut cannot change types.

let mut word = "hello";

word = word.len();error[E0308]: mismatched types

--> src/main.rs:3:12

|

3 | word = word.len();

| ^^^^^^^^^^ expected `&str`, found `usize`

How do we define a constant in Rust?

Can we shadow a constant? T(rue) or F(alse)

What do we use to change the type of an immutable variable once it has been defined?

Will the code "CONST word = "yes"" compile? T(rue) or F(alse)

We have "let word = "hello"", how do we get the length of the variable?

In Rust we'll very often see the compiler complain that our variables and functions aren't type hinted. We saw type hints with CONST earlier. A type hint defines what the data type of a variable is at compile time.

In Rust we'll very often see the compiler complain that our variables and functions aren't type hinted. We saw type hints with CONST earlier. A type hint defines what the data type of a variable is at compile time.

let ports: u32 = 65535

The : u32 states that the variable ports is of size u32.

The u in the integer means unsigned, and the 32 is how many bits it has.

Unsigned integers can only ever be positive, signed integers can be both positive and negative.

Integers range from 16 bits up to 128 bits. Some operating systems can't use integers higher than u32, and using such large integer types may slow down the program on some systems.

| 8-bit | i8 | u8 |

| 16-bit | i16 | u16 |

| 32-bit | i32 | u32 |

| 64-bit | i64 | u64 |

| 128-bit | i128 | u128 |

| arch | isize | usize |

As you explore Rust, you will come across many, many different data types. It would be foolish for me to try and teach them all, so I have elected to teach only what I believe will help you understand Rust right now.

We've seen how integers work, but what about strings?

Strings

There are two types of strings in Rust. String and &str.

String is a growable allocated data structure whereas str is an immutable fixed-length string somewhere in memory.

&str is a string slice of string.

Strings are confusing for beginners in Rust, but these are the core principles. Here's a list to the relevant Rust book page on Strings for more information.

Given the number 65536, what is the smallest unsigned datatype we can fit this into?

What's the smallest sized signed integer in rust?

Create a mutable u32 variable called "tryhackme" and assign it the number 9

What data type is used to represent a string slice?

Let's say you had a variable, X. You wanted to typehint the variable as a string. What would you write? Include X in the variable but not the let or = parts.

We've already seen a special kind of function earlier, the main function.

The main function is the first function called of the main file, which is the first file called.

Every binary file written in Rust needs a main file, and every main file needs a main function.

Functions in Rust are defined as:

fn hello() -> u16{

println!("hello!");

6

}

The main function is the same as this, but in a binary file it doesn't return anything.

fn main(){

println!("I do not return!")

}

Now, you might have noticed in the hello function that we have a 6 on the end.

"What???" I can hear you saying.

Well, Rust returns the final expression of the function.

Alternatively, we can use the return statement to return earlier. However, it's not very nice to use it to return the value at the end of the function — Rustaceans and Clippy will dislike that 😢

6 is an expression that returns 6, so our hello function returns 6.

Our main function does not return anything, which is the way it should be.

Let's add some arguments to our functions.

fn print_name(name: String){

println!("{}", name);

}

Our function arguments have to include the type of each argument.

Now let's try to make this function return something.

fn print_name(name: String) -> u16{

println!("{}", name);

6;

}When we return data, we have to type hint the type of data that is being returned.

This may seem annoying, but it makes writing clean code so much easier.

Compare these two functions, one in Pythonic pseudocode and one in Rust. Note: we only have the definitions.

def to_ip_address(ip):

Now in Rust:

fn to_ip_address(ip: String) -> IpAddr{

By just adding the types we can clearly see we are taking in a string, and turning it into an IP address.

With proper function naming and typehints, we can tell what most functions do just from their definitions. How's that for clean code 😜

Question 1

fn hello(){

8172192: u16;

}

Question 2

fn return(){

6;

}

Question 3

fn test(name) {

println!("{}", name);

}

test("bee");

Will example 2 run? T(rue) or F(alse)

What type should we give to the argument for question 3?

Every function need to return something. T(rue) or F(alse)

What keyword do we use to return early from a function?

You nest a function named main, inside another function named main. Will this run? T(rue) or F(alse)

There are 3 loops in Rust.

loop

The loop keyword loops forever or until we explicitly tell it to stop.

fn main(){

loop {

println!("TryHackMe Rocks!");

}

}

We can either break with ctrl+c or we can tell Rust to break with break

fn main(){

loop {

println!("TryHackMe Rocks!");

break;

}

}

Conditional While Loops

Rust also has while loops, which loop while a condition is true.

Look at this example for some code, taken from the Rust Book:

fn main() {

let mut number = 3;

while number != 0 {

println!("{}!", number);

number -= 1;

}

println!("LIFTOFF!!!");

}

For loops

Rust also has for loops, which we can use to iterate over elements of a collection.

fn main() {

let a = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50];

for element in a.iter() {

println!("the value is: {}", element);

}

}Note the a.iter. We turn a into an iterable using this. This will become very important to us very soon.

Simplest keyword to make an infinite loop?

Turn let a = [10, 20]; into something we can iterate over.

While loops can also be infinite. T(rue) or F(alse).

This task is copied from my blog, where I wrote about Zero Cost Abstractions once.

Rust has this really cool thing called Zero Cost Abstractions. It’s also a thing in other low level languages, but being a Python Surfer Dude I haven’t come across it before.

Zero cost abstraction is:

"What you don’t use, you don’t pay for. And what you do use, you couldn’t do any better if you coded by hand."

Let’s talk about the 2 parts of this sentence.

"What you don’t use, you don’t pay for."

The language shouldn’t have a global cost for a feature that isn’t used. Let’s say to use a for loop, the language needs to have some massive 1gb file that slows down everything else. If we never use a for loop, we still pay for the for loop!

"And what you do use, you couldn’t do any better if you coded by hand."

Here’s the kicker.

Say you wrote some code, a function that calculated Fibonacci numbers. And you compiled this code down into assembly.

Now let’s say you hand-write assembly to do the same function — calculate Fibonacci numbers but this time in assembly.

Handwriting it in assembly would mean we would either gain no performance, or we would lose performance.

By using zero cost abstractions, we write abstracted code (not handwritten assembly) and we couldn’t do any better if we tried to hand-write assembly. Now that’s cool!

Now, let's explore iterators.

Iterators are a way of processing a series of items with Rust, much like a for loop.

We saw earlier a.iter(). This code turns the variable a into an iterator over the items of a. But this code by itself doesn't do anything useful.

This is because iterators are lazy. You have to tell them to do something to get values from them.

Let's take a look at a real example.

let a = vec![1, 2, 3];

let a_iter = a.iter();

for val in a_iter {

println!("The value is {}, val);

}We make the iterator do something by calling it in this for loop.

Now we can make the code do something and consume the iter using some nifty functional programming skills. To square every number in an iterator, and then to sum it we can do:

let a = vec![1, 2, 3];

a.iter()

.map(|&i| i * i

.sum()

Note, in Rust, we can separate applications of methods with new lines.

This is just a small portion of what iterators can do. Read the entire chapter on them from the Rust Book here.

However, let's get back to the important tasks at hand. Zero cost abstractions.

Iterators are zero cost abstractions in Rust. For loops are not. This is according to the Rust Book.

By using iterators, we are taking advantage of the fantastic zero cost abstraction. Speeding up our entire program.

Iterators are lazy. T(rue) or F(alse).

For loops are explicitly mentioned in the Rust book as zero cost abstractions. T(rue) or F(alse).

Zero Cost Abstractions are common in high level languages like Python or JavaScript T(rue) or F(alse).

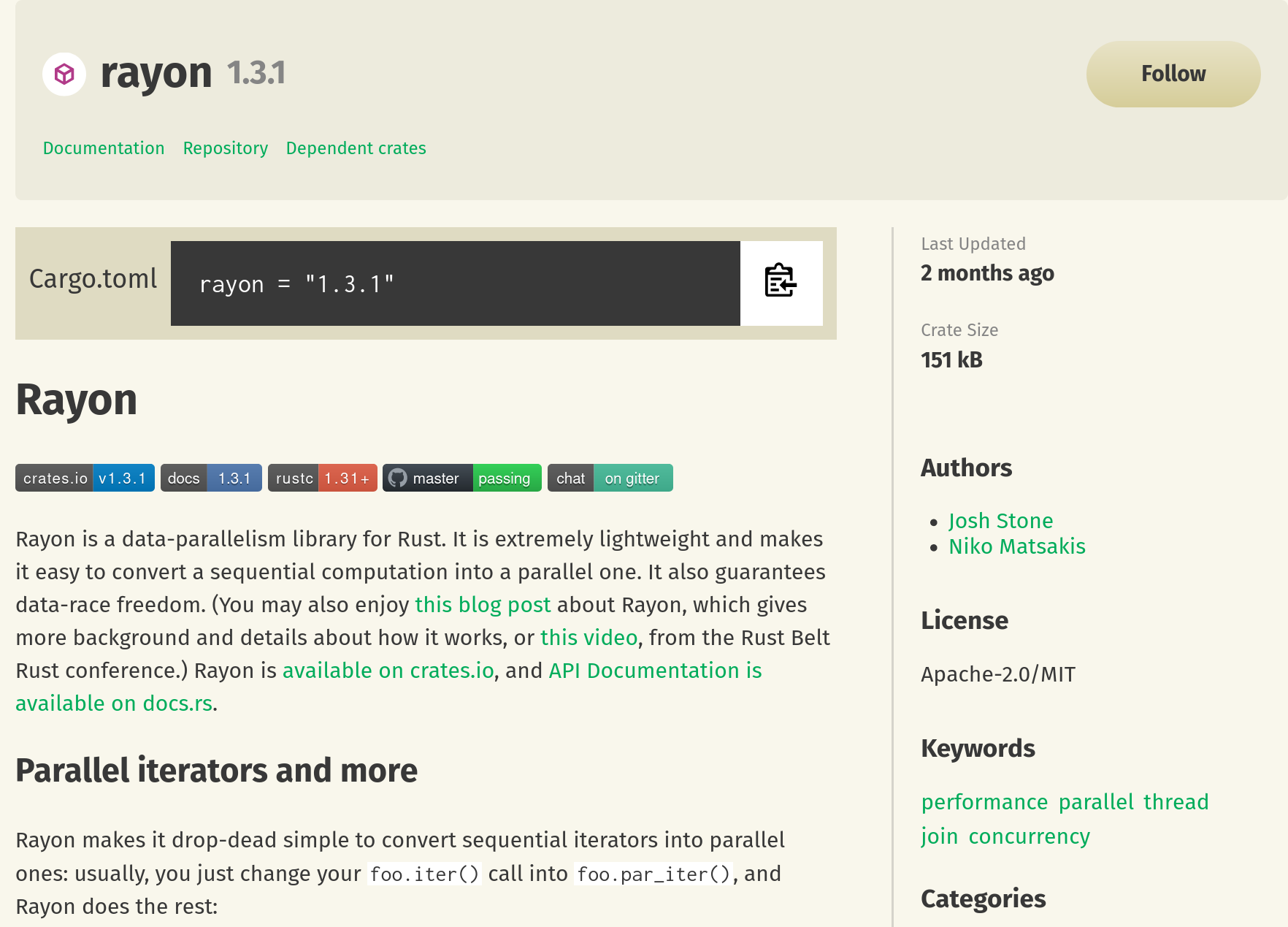

Rayon is an external crate for Rust, and normally I wouldn't include external libraries. However, it's just so awesome and fits so well with the last few tasks I just had to mention it.

Rayon makes multi threading easy. No, really. It's extremely easy.

Go to Crates.io and copy the big black box containing the crate with the version number.

Now go into cargo.toml, and include it in the dependencies section. Just copy and paste it across.

Now go into cargo.toml, and include it in the dependencies section. Just copy and paste it across.

Okay, now let's take our iter in the last task and make it multi threaded.

fn sum_of_squares(input: &[i32]) -> i32 {

input.iter()

.map(|&i| i * i)

.sum()

}

This is our previous code.

use rayon::prelude::*;

fn sum_of_squares(input: &[i32]) -> i32 {

input.par_iter() // <-- just change that!

.map(|&i| i * i)

.sum()

}

This is our multi-threaded code.

Look at how easy that is! We change iter() into par_iter() and we're done. We're now multi threaded.

How do we tell Rust to include an external crate into our program? What file do we place this information in?

Turn a.iter() into a multi threaded parallel iter using Rayon

What website do we go to for Crates?

If statements work exactly like how you'd expect.

If statements work exactly like how you'd expect.

let var = 6;

if var == 6{

println!("oh no the var is 6");

}

else {

println!("yay the var isn't 6");

}

But, Rust lets us do cool things with if statements. Such as assigning to a variable based on an if statement.fn func() -> i8{

9

}

let var = 6 + func();

let result = if var == 6 {15} else {200};

let output =

if var == 15 {

println!("it is 15");

9;

}else {

println!("it is not 15");

10;

};

And that's it. Nothing really to it, it's exactly like every other language.

Now we get into the inner-workings of Rust, the thing that helps keep it safe. Error handling.

Now we get into the inner-workings of Rust, the thing that helps keep it safe. Error handling.

In Rust, anything that can error will return a result. Specifically Result<T, E>. T is the result you are looking for, E is the error.

enum Result<T, E> {

Ok(T),

Err(E),

}

Anytime you open a file, the file might not be there or it may fail to open the file successfully. It will return a Result, and you will have to deal with it that way.

In Python, exception handling is given to the user. If you want to open a file, go ahead. But don't forget to write an exception for if the file isn't there!

But in Rust, no matter what (unless you explicitly tell the compiler to ignore it) errors must be handled.

Let's look at an example.

use std::fs::File;

fn main() {

let f = File::open("hello.txt");

}

Here we go to open a file. The file isn't stored in f, what is stored is actually a Result enum.

There are 2 ways to check if something returns an result.

- Rust Analyzer will tell us what the return type is.

- We assign a type we know is wrong, and the compiler will tell us.

If we assigned let f: u32 = File::open("hello.txt"); the compiler will tell us.

--> src/main.rs:4:18

|

4 | let f: u32 = File::open("hello.txt");

| --- ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ expected `u32`, found enum `std::result::Result`

| |

| expected due to this

|

= note: expected type `u32`

found enum `std::result::Result<std::fs::File, std::io::Error>`So now we know that we have to handle the error, but the question is how.

I'm going to show you 3 ways.

1. UnwrapUnwrap is the easiest to implement. It tells Rust "I'm pretty sure this won't fail so just go ahead and take the value". If it does fail, well, Rust panics!

use std::fs::File;

fn main() {

let f = File::open("hello.txt").unwrap();

}2. Match

Match is how you'd expect this to work, if you're used to Python.

We do one thing for an Ok, and we do another for an Error.

use std::fs::File;

fn main() {

let f = File::open("hello);

match f {

Ok(file) => file,

Err(_) => panic!("Couldn't open file."),

}

}If the result is Ok, that means the result is successful and we can just take the file.

If it's an Err that means an error occurred and we need to do something about it. In this case, the program panics.

3. ?

The ? operator states "if the result is Ok, carry on in this function. Else if it is an Err, propagate it back up the stack to the function that called me. "

To illustrate this, let's look at this example I took from a Rust blog post.

fn read_username_from_file() -> Result<String, io::Error> {

let f = File::open("username.txt");

let mut f = match f {

Ok(file) => file,

Err(e) => return Err(e),

};

let mut s = String::new();

match f.read_to_string(&mut s) {

Ok(_) => Ok(s),

Err(e) => Err(e),

}

}We have 2 matches in this code. A bit unruly. Ideally if we fail to open the file, or fail to read to string we propagate a single error back up the stack saying that this function failed.

If it didn't, we should return the Ok result. That way, the function that called us will receive a Result type that it can more easily handle, and without us dealing with multiple match statements.

fn read_username_from_file() -> Result<String, io::Error> {

let mut f = File::open("username.txt")?;

let mut s = String::new();

f.read_to_string(&mut s)?;

Ok(s)

}Conclusion

This is one of the most important concepts in Rust. Errors normally do not happen, because every error has to be dealt with in some way. This helps keep your code safe.

Write the datatype of a generic Result with type hints

We're in a function and we get given a Result enum. If the Result is okay we want to continue working on it in this function. If the result is Err we want to return to the parent function with Err. What should we use?

We're certain our result will always return Ok, what should we use?

Challenge file 1.

"M3I6r2IbMzq9" is the text.

The text is encrypted with:

plaintext -> ROT13 -> base64 -> rot13

Go the opposite way and decrypt the file.

rot13 -> base64 -> ROT13 -> plaintext

You'll notice it's the same order either way, so you don't have to worry about order. Just make sure ROT13 is on the inside.

You might run into lifetime borrow checker issues.

Here's some hints in case you do:

1. Google is your friend.

2. https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch04-02-references-and-borrowing.html

3. Stop trying to do so many things at once. Break it down to the bare necessities and slowly build back up to see what causes the errors.

And that's it! Rust is an extremely cool language, quite safe and very fast. But, there is one major tradeoff we have to make.

Rust does not support inheritance. That means we have to individually implement behaviour for each data type we create.

However, this is also an advantage for security reasons. As it gives us time to think about what we are doing. We might want different hashing algorithms for employees in different departments, for example.

If you want to write unsafe Rust, check out this part of the Rust book. I didn't talk about this in the room as unsafe Rust is, by nature, unsafe and not very well suited to blue team operations.

I'm going to share with you some cool resources on Rust.

- I wrote a blog post about packaging Rust apps for multiple systems here. So if you ever want to distribute for Arch, Homebrew, Debian or more click here.

- A link to Rust community, which contains a link to their official Discord where they discuss the language itself.

- The Rust subreddit

- Cool Rust CLI alternatives to popular commands

- https://github.com/rust-unofficial/awesome-rust

- https://github.com/ctjhoa/rust-learning

Ready to learn Cyber Security? Create your free account today!

TryHackMe provides free online cyber security training to secure jobs & upskill through a fun, interactive learning environment.

Already have an account? Log in