To access material, start machines and answer questions login.

Linux has long been a leader in servers and embedded systems, and now its use is even more widespread with the growth of cloud adoption. As a SOC analyst, you are now very likely to investigate Linux alerts and incidents, either from traditional on-premises servers or from cloud-native containerized workloads. In this room, you will explore the most common Linux logs sent to SIEM and learn how to view them directly on-host.

Learning Objectives

- Explore authentication, runtime, and system logs on Linux

- Learn the commands and pitfalls when working with logs

- Uncover how tools like auditd monitor and report the events

- Practice every learned log source in the attached VM

Recommended Rooms

- Complete the Linux Fundamentals module

- Complete the Linux Shells room

- Learn the Logs Fundamentals

Machine Access

Before moving forward, start the lab by clicking the Start Machine button below. The machine will start in split view and will take about two minutes to load. In case the machine is not visible, you can click the Show Split View button at the top of the task. You may need to work as the root user for some tasks. To switch to root on the VM, please run sudo su.

Set up your virtual environment

Credentials

Alternatively, you can access the VM from your own VPN-connected machine with the credentials below:

Let's start!

Log Format

Contrary to a common belief, Linux-based systems are not immune to malware. Moreover, Linux-targeted intrusions are a growing problem. Thus, as a SOC analyst, you will often need to investigate Linux alerts, and for this, you need to understand how its logging works. Now, let's clarify a couple of things and move on!

- By Linux, the room refers to Linux distributions like Debian, Ubuntu, CentOS, or RHEL

- The room focuses on Linux servers without a GUI and does not explain desktop logging

Working With Logs

Unlike in Windows, Linux logs most events into plain text files. This means you can read the logs via any text editor without the need for specialized tools like Event Viewer. On the other hand, default Linux logs are less structured as there are no event codes and strict log formatting rules. Most Linux logs are located in the /var/log folder, so let's start the journey by checking the /var/log/syslog file - an aggregated stream of various system events:

root@thm-vm:~$ cat /var/log/syslog | head

[...]

2025-08-13T13:57:49.388941+00:00 thm-vm systemd-timesyncd[268]: Initial clock synchronization to Wed 2025-08-13 13:57:49.387835 UTC.

2025-08-13T13:59:39.970029+00:00 thm-vm systemd[888]: Starting dbus.socket - D-Bus User Message Bus Socket...

2025-08-13T14:02:22.606216+00:00 thm-vm dbus-daemon[564]: [system] Successfully activated service 'org.freedesktop.timedate1'

2025-08-13T14:05:01.999677+00:00 thm-vm CRON[1027]: (root) CMD (command -v debian-sa1 > /dev/null && debian-sa1 1 1)

[...]

Filtering Logs

You will see thousands of events when reading the syslog file on the attached VM, but only a few are useful for SOC. That's why you must filter logs and narrow down your search as much as possible. For example, you can use the "grep" command to filter for the "CRON" keyword and see only the cronjob logs:

# Or "grep -v CRON" to exclude "CRON" from results

root@thm-vm:~$ cat /var/log/syslog | grep CRON

2025-08-13T14:17:01.025846+00:00 thm-vm CRON[1042]: (root) CMD (cd / && run-parts --report /etc/cron.hourly)

2025-08-13T14:25:01.043238+00:00 thm-vm CRON[1046]: (root) CMD (command -v debian-sa1 > /dev/null && debian-sa1 1 1)

2025-08-13T14:30:01.014532+00:00 thm-vm CRON[1048]: (root) CMD (date > mycrondebug.log)

Discovering Logs

Lastly, let's say you hunt for all user logins, but don't know where to look for them. Linux system logs are stored in the /var/log/ folder in plain text, so you can simply grep for related keywords like "login", "auth", or "session" in all log files there and narrow down your next searches:

# List what's logged by your system (/var/log folder)

root@thm-vm:~$ ls -l /var/log

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Aug 12 16:41 apt

drwxr-x--- 2 root adm 4096 Aug 12 12:40 audit

-rw-r----- 1 syslog adm 45399 Aug 13 15:05 auth.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1361277 Aug 12 16:41 dpkg.log

drwxr-sr-x+ 3 root systemd-journal 4096 Oct 22 2024 journal

-rw-r----- 1 syslog adm 214772 Aug 13 13:57 kern.log

-rw-r----- 1 syslog adm 315798 Aug 13 15:05 syslog

[...]

# Search for potential logins across all logs (/var/log)

root@thm-vm:~$ grep -R -E "auth|login|session" /var/log

[...]

Logging Caveats

Unlike Windows, Linux allows you to easily change log format, verbosity, and storage location. With hundreds of Linux distributions, each known to slightly customize logging, be prepared that the logs in this room may look different on your system, or might not exist at all.

Use the /var/log/syslog file on the VM to answer the questions.

Which time server domain did the VM contact to sync its time?

What is the kernel message from Yama in /var/log/syslog?

Authentication Logs

The first and often the most useful log file you want to monitor is /var/log/auth.log (or /var/log/secure on RHEL-based systems). Although its name suggests it contains authentication events, it can also store user management events, launched sudo commands, and much more! Let's start with the log file format:

Login and Logout Events

There are many ways users authenticate into a Linux machine: locally, via SSH, using "sudo" or "su" commands, or automatically to run a cron job. Each successful logon and logoff is logged, and you can see them by filtering the events containing the "session opened" or "session closed" keywords:

root@thm-vm:~$ cat /var/log/auth.log | grep -E 'session opened|session closed'

# Local, on-keyboard login and logout of Bob (login:session)

2025-08-02T16:04:43 thm-vm login[1138]: pam_unix(login:session): session opened for user bob(uid=1001) by bob(uid=0)

2025-08-02T19:23:08 thm-vm login[1138]: pam_unix(login:session): session closed for user bob

# Remote login examples of Alice (via SSH and then SMB)

2025-08-04T09:09:06 thm-vm sshd[839]: pam_unix(sshd:session): session opened for user alice(uid=1002) by alice(uid=0)

2025-08-04T12:46:13 thm-vm smbd[1795]: pam_unix(samba:session): session opened for user alice(uid=1002) by alice(uid=0)

root@thm-vm:~$ cat /var/log/auth.log | grep -E 'session opened|session closed'

# Traces of some cron job launch running as root (cron:session)

2025-08-06T19:35:01 thm-vm CRON[41925]: pam_unix(cron:session): session opened for user root(uid=0) by root(uid=0)

2025-08-06T19:35:01 thm-vm CRON[3108]: pam_unix(cron:session): session closed for user root

# Carol running "sudo su" to access root (sudo:session)

2025-08-07T09:12:32 thm-vm sudo: pam_unix(sudo:session): session opened for user root(uid=0) by carol(uid=1003)

In addition to the system logs, the SSH daemon stores its own log of successful and failed SSH logins. These logs are sent to the same auth.log file, but have a slightly different format. Let's see the example of two failed and one successful SSH logins:

root@thm-vm:~$ cat /var/log/auth.log | grep "sshd" | grep -E 'Accepted|Failed'

# Common SSH log format: <is-successful> <auth-method> for <user> from <ip>

2025-08-07T11:21:25 thm-vm sshd[3139]: Failed password for root from 222.124.17.227 port 50293 ssh2

2025-08-07T14:17:40 thm-vm sshd[3139]: Failed password for admin from 138.204.127.54 port 52670 ssh2

2025-08-09T20:30:51 thm-vm sshd[1690]: Accepted publickey for bob from 10.19.92.18 port 55050 ssh2: <key>

Miscellaneous Events

You can also use the same log file to detect user management events. This is easy if you know basic Linux commands: If useradd is a command to add new users, just look for a "useradd" keyword to see user creation events! Below is an example of what you can see in the logs: password change, user deletion, and then privileged user creation.

root@thm-vm:~$ cat /var/log/auth.log | grep -E '(passwd|useradd|usermod|userdel)\['

2023-02-01T11:09:55 thm-vm passwd[644]: password for 'ubuntu' changed by 'root'

2025-08-07T22:11:11 thm-vm userdel[1887]: delete user 'oldbackdoor'

2025-08-07T22:11:29 thm-vm useradd[1878]: new user: name=backdoor, UID=1002, GID=1002, shell=/bin/sh

2025-08-07T22:11:54 thm-vm usermod[1906]: add 'backdoor' to group 'sudo'

2025-08-07T22:11:54 thm-vm usermod[1906]: add 'backdoor' to shadow group 'sudo'

Lastly, depending on system configuration and installed packages, you may encounter interesting or unexpected events. For example, you may find commands launched with sudo, which can help track malicious actions. In the example below, the "ubuntu" user used sudo to stop EDR, read firewall state, and finally access root via "sudo su":

root@thm-vm:~$ cat /var/log/auth.log | grep -E 'COMMAND='

2025-08-07T11:21:49 thm-vm sudo: ubuntu : TTY=pts/0 ; [...] COMMAND=/usr/bin/systemctl stop edr

2025-08-07T11:23:18 thm-vm sudo: ubuntu : TTY=pts/0 ; [...] COMMAND=/usr/bin/ufw status numbered

2025-08-07T11:23:33 thm-vm sudo: ubuntu : TTY=pts/0 ; [...] COMMAND=/usr/bin/su

Continue with the VM and use the /var/log/auth.log file.

Which IP address failed to log in on multiple users via SSH?

Which user was created and added to the "sudo" group?

Generic System Logs

Linux keeps track of many other events scattered across files in /var/log: kernel logs, network changes, service or cron runs, package installation, and many more. Their content and format can differ depending on the OS, and the most common log files are:

/var/log/kern.log: Kernel messages and errors, useful for more advanced investigations/var/log/syslog (or /var/log/messages): A consolidated stream of various Linux events/var/log/dpkg.log (or /var/log/apt): Package manager logs on Debian-based systems/var/log/dnf.log (or /var/log/yum.log): Package manager logs on RHEL-based systems

The listed logs are valuable during DFIR, but are rarely seen in a daily SOC routine as they are often noisy and hard to parse. Still, if you want to dive deeper into how these logs work, check out the Linux Logs Investigations DFIR room.

App-Specific Logs

In SOC, you might also monitor a specific program, and to do this effectively, you need to use its logs. For example, analyze database logs to see which queries were run, mail logs to investigate phishing, container logs to catch anomalies, and web server logs to know which pages were opened, when, and by whom. You will explore these logs in the upcoming modules, but to give an overview, here is an example from the typical Nginx web server logs:

root@thm-vm:~$ cat /var/log/nginx/access.log

# Every log line corresponds to a web request to the web server

10.0.1.12 - - [11/08/2025:14:32:10 +0000] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 3022

10.0.1.12 - - [11/08/2025:14:32:14 +0000] "GET /login HTTP/1.1" 200 1056

10.0.1.12 - - [11/08/2025:14:33:09 +0000] "POST /login HTTP/1.1" 302 112

10.0.4.99 - - [11/08/2025:17:11:20 +0000] "GET /images/logo.png HTTP/1.1" 200 5432

10.0.5.21 - - [11/08/2025:17:56:23 +0000] "GET /admin HTTP/1.1" 403 104

Bash History

Another valuable log source is Bash history - a feature that records each command you run after pressing Enter. By default, commands are first stored in memory during your session, and then written to the per-user ~/.bash_history file when you log out. You can open the ~/.bash_history file to review commands from previous sessions or use the history command to view commands from both your current and past sessions:

ubuntu@thm-vm:~$ cat /home/ubuntu/.bash_history

echo "hello" > world.txt

nano /etc/ssh/sshd_config

sudo su

ubuntu@thm-vm:~$ history

1 echo "hello" > world.txt

2 nano /etc/ssh/sshd_config

3 sudo su

4 ls -la /home/ubuntu

5 cat /home/ubuntu/.bash_history

6 history

Although the Bash history file looks like a vital log source, it is rarely used by SOC teams in their daily routine. This is because it does not track non-interactive commands (like those initiated by your OS, cron jobs, or web servers) and has some other limitations. While you can configure it to be more useful, there are still a few issues you should know about:

# Attackers can simply add a leading space to the command to avoid being logged

ubuntu@thm-vm:~$ echo "You will never see me in logs!"

# Attackers can paste their commands in a script to hide them from Bash history

ubuntu@thm-vm:~$ nano legit.sh && ./legit.sh

# Attackers can use other shells like /bin/sh that don't save the history like Bash

ubuntu@thm-vm:~$ sh

$ echo "I am no longer tracked by Bash!"

According to the VM's package manager logs,

which version of unzip was installed on the system?

What is the flag you see in one of the users' bash history?

Runtime Monitoring

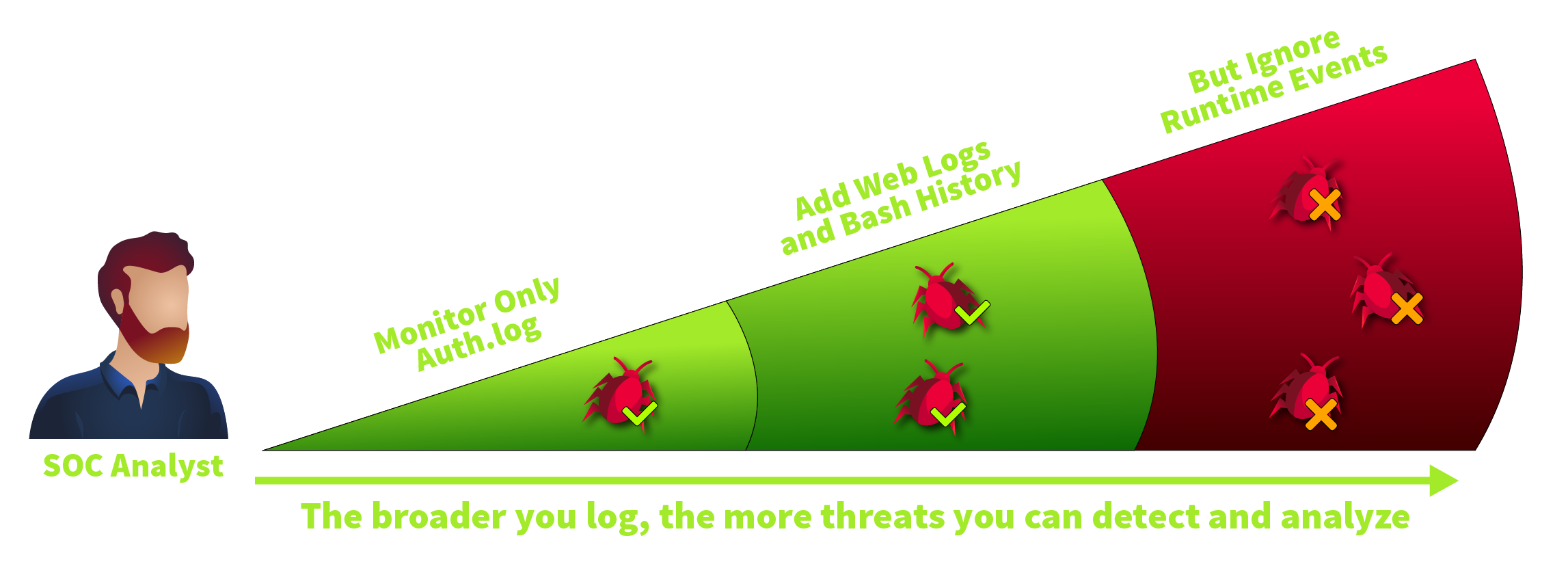

Up to this point, you have explored various Linux log sources, but none can reliably answer questions like "Which programs did Bob launch today?" or "Who deleted my home folder, and when?". That's because, by default, Linux doesn't log process creation, file changes, or network-related events, collectively known as runtime events. Interestingly, Windows faces the same limitation, which is why in the Windows Logging for SOC room we had to use an additional tool: Sysmon. In Linux, we'll take a similar approach.

System Calls

Before moving on, let's explore a core OS concept that might help you understand many other topics: system calls. In short, whenever you need to open a file, create a process, access the camera, or request any other OS service, you make a specific system call. There are over 300 system calls in Linux, like execve to execute a program. Below is a high-level flowchart of how it works:

Why do you need to know about system calls? Well, all modern EDRs and logging tools rely on them - they monitor the main system calls and log the details in a human-readable format. Since there is nearly no way for attackers to bypass system calls, all you have to do is choose the system calls you'd like to log and monitor. In the next task, you will try it in practice using auditd.

Which Linux system call is commonly used to execute a program?

Can a typical program open a file or create a process bypassing system calls? (Yea/Nay)

Audit Daemon

Auditd (Audit Daemon) is a built-in auditing solution often used by the SOC team for runtime monitoring. In this task, we will skip the configuration part and focus on how to read auditd rules and how to interpret the results. Let's start from the rules - instructions located in /etc/audit/rules.d/ that define which system calls to monitor and which filters to apply:

Monitoring every process, file, and network event can quickly produce gigabytes of logs each day. But more logs don't always mean better detection since an attack buried in a terabyte of noise is still invisible. That's why SOC teams often focus on the highest-risk events and build balanced rulesets, like this one or the example you saw above.

Using Auditd

You can view the generated logs in real time in /var/log/audit/audit.log, but it is easier to use the ausearch command, as it formats the output for better readability and supports filtering options. Let's see an example based on the rules from the example above by searching events matching the "proc_wget" key:

root@thm-vm:~$ ausearch -i -k proc_wget

----

type=PROCTITLE msg=audit(08/12/25 12:48:19.093:2219) : proctitle=wget https://files.tryhackme.thm/report.zip

type=CWD msg=audit(08/12/25 12:48:19.093:2219) : cwd=/root

type=EXECVE msg=audit(08/12/25 12:48:19.093:2219) : argc=2 a0=wget a1=https://files.tryhackme.thm/report.zip

type=SYSCALL msg=audit(08/12/25 12:48:19.093:2219) : arch=x86_64 syscall=execve [...] ppid=3752 pid=3888 auid=ubuntu uid=root tty=pts1 exe=/usr/bin/wget key=proc_wget

The terminal above shows a log of a single "wget" command. Here, auditd splits the event into four lines: the PROCTITLE shows the process command line, CWD reports the current working directory, and the remaining two lines show the system call details, like:

pid=3888, ppid=3752: Process ID and Parent Process ID. Helpful in linking events and building a process treeauid=ubuntu: Audit user. The account originally used to log in, whether locally (keyboard) or remotely (SSH)uid=root: The user who ran the command. The field can differ from auid if you switched users with sudo or sutty=pts1: Session identifier. Helps distinguish events when multiple people work on the same Linux serverexe=/usr/bin/wget: Absolute path to the executed binary, often used to build SOC detection ruleskey=proc_wget: Optional tag specified by engineers in auditd rules that is useful to filter the events

File Events

Now, let's look at the file events matching the "file_sshconf" key. As you may see from the terminal below, auditd tracked the change to the /etc/ssh/sshd_config file via the "nano" command. SOC teams often set up rules to monitor changes in critical files and directories (e.g., SSH configuration files, cronjob definitions, or system settings)

root@thm-vm:~$ ausearch -i -k file_sshconf

----

type=PROCTITLE msg=audit(08/12/25 13:06:47.656:2240) : proctitle=nano /etc/ssh/sshd_config

type=CWD msg=audit(08/12/25 13:06:47.656:2240) : cwd=/

type=PATH msg=audit(08/12/25 13:06:47.656:2240) : item=0 name=/etc/ssh/sshd_config [...]

type=SYSCALL msg=audit(08/12/25 13:06:47.656:2240) : arch=x86_64 syscall=openat [...] ppid=3752 pid=3899 auid=ubuntu uid=root tty=pts1 exe=/usr/bin/nano key=file_sshconf

Auditd Alternatives

You might have noticed an inconvenient output of auditd - although it provides a verbose logging, it is hard to read and ingest into SIEM. That's why many SOC teams resort to the alternative runtime logging solutions, for example:

- Sysmon for Linux: A perfect choice if you already work with Sysmon and love XML

- Falco: A modern, open-source solution, ideal for monitoring containerized systems

- Osquery: An interesting tool that can be broadly used for various security purposes

- EDRs: Most EDR solutions can track and monitor various Linux runtime events

The key to remember is that all listed tools work on the same principle - monitoring system calls. Once you've understood system calls, you will easily learn all the mentioned tools. This knowledge also helps you to handle advanced scenarios, like understanding why certain actions were logged in a specific way or not logged at all.

Now, try to uncover a threat actor with process creation logs! For this task, continue with the VM and use auditd logs to answer the questions.

You may need to use ausearch -i and grep commands for this task.

When was the secret.thm file opened for the first time? (MM/DD/YY HH:MM:SS)

Note: Access to this file is logged with the "file_thmsecret" key.

What is the original file name downloaded from GitHub via wget?

Note: Wget process creation is logged with the "proc_wget" key.

Which network range was scanned using the downloaded tool?

Note: There is no dedicated key for this event, but it's still in auditd logs.

Great job exploring the Linux log sources! In the upcoming rooms, you will put this knowledge into action to trace and investigate a variety of threats targeting Linux systems. From the Initial Access to the final attack steps, you may need all learned log sources to fully uncover the breaches.

Key Takeaways

- Linux logging can be chaotic, but it often stores enough details to detect the threat

- Logs are kept in

/var/log/folder by default and are usually stored in plain text - The top three log sources for SOC are auth.log, app-specific logs, and runtime logs

- Bash history is unreliable for SOC; better use auditd or an alternative solution

Complete the room!

Ready to learn Cyber Security? Create your free account today!

TryHackMe provides free online cyber security training to secure jobs & upskill through a fun, interactive learning environment.

Already have an account? Log in